A General Theory of Love

“I have always felt that a human being could only be saved by another human being. I am aware that we do not save each other very often. But I am also aware that we save each other some of the time.” —James Baldwin

Artists, poets, musicians, and painters have used their crafts for thousands of years to explain this tiny, mysterious thing called love. Recently, scientists have been jumping on the trend. Love, as it turns out, is not just a line by a romantic poet, but a condition a doctor can measure. “A relationship is a physiologic process, as real and as potent as any pill or surgical procedure.”

I’m learning about this from the book The General Theory of Love, which my therapist recommended to me. So, below is my attempt at writing a book review.

Our nervous systems are not self-contained: from the moment we’re born, our brains link with those closest to us and shape our emotional blueprint. We learn how to feel through others. Heal through others. And when those others vanish, so does our stability.

“Take a puppy away from his mother, place him alone in a wicker pen, and you will witness the universal mammalian reaction to the rupture of an attachment bond—a reflection of the limbic architecture mammals share. Short separations provoke an acute response known as protest, while prolonged separations yield the physiologic state of despair. A lone puppy first enters the protest phase. He paces tirelessly, scanning his surroundings from all vantage points, barking, scratching vainly at the floor. He makes energetic and abortive attempts at scaling the walls of his prison, tumbling into a heap with each failure. He lets out a piteous whine, high-pitched and grating. Every aspect of his behavior broadcasts his distress—the same discomfort that all social mammals show when deprived of those to whom they are attached. Even young rats evidence protest: when their mother is absent, they emit nonstop ultrasonic cries, a plaintive chorus inaudible to our dull ape ears.”

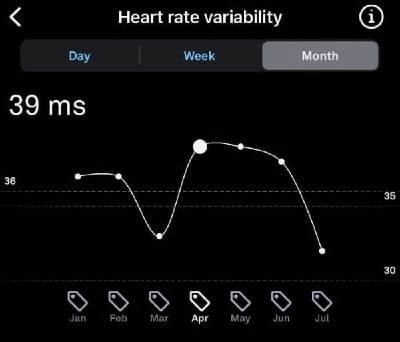

Extended and sudden separation can lead to cortisol surges, immune suppression, cardiovascular dysfunction, and cognitive disarray. It’s not a metaphor. It’s measurable. I saw it myself during a prolonged rupture; my Oura ring tracked my heart rate dropping, just like that abandoned puppy. (My heart. My poor little pup heart). I felt it in my energy, in my cognitive abilities. We are not so different.

All of this makes sense. Love is not self-contained. To love is to recognize that something beyond yourself exists, and that something has power over you. Adults remain social animals: we continue to require a source of stabilization outside ourselves (despite how independent the world wants us to believe). Signs of this exist in our daily lives. People hug each other on departures and arrivals—an act so familiar we might think it nothing more than a custom. But this style of embrace contains evidence of attachment: an imposed separation, or the threat of one, reflexively prompts us to reestablish skin-to-skin contact.

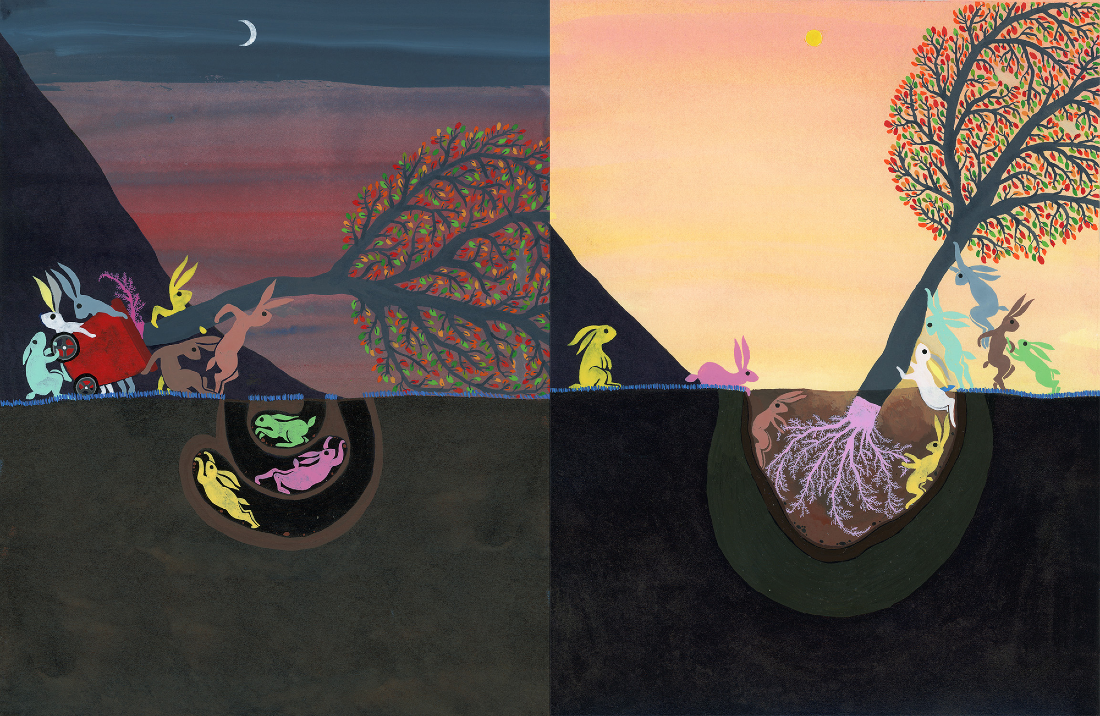

In connection, we revise one another. Who we become is shaped, in part, by whom we love. That’s the beauty and the burden of connection: its power to heal—and its power to harm.

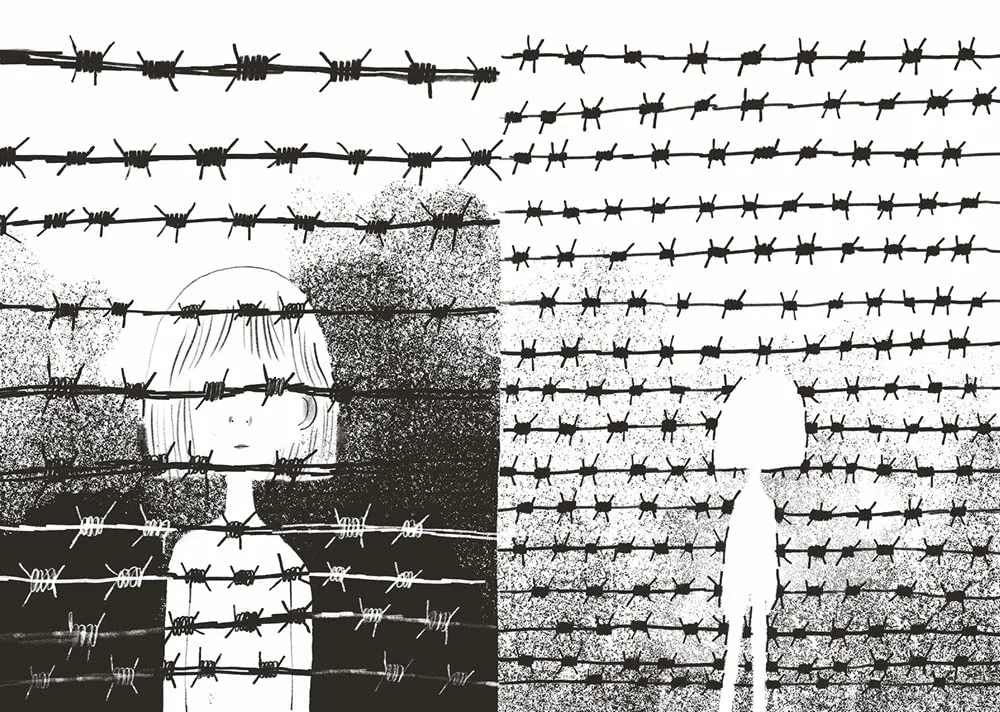

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” I think the same goes for connection. Healthy bonds tend to follow similar rhythms: attunement, presence, care, repair, safety. But disconnection? That comes in infinite forms. And of them all, the cruelest is what I can only describe as the coldest corner of the emotional underworld of Greenland. Described in The General Theory of Love as: “Expulsion from the company of others is the cruelest punishment human beings can devise.” Or what Virginia Woolf once felt as: “A profound loneliness, a sense of being cut off from the world, from other people, from oneself.”

Let me explain that more: I think of relationships as homes. You move in slowly, with care. You fill them with shared language, familiar gestures, and memories built into the walls.

But instead of moving out with care, you’re kicked out without a word.

This is one party locking the door, without warning, without goodbye, while the other is still standing on the threshold. One gets peace. One gets control. The other is left in the open, disoriented and exposed, knocking on the door of a house they thought they still lived in. They don’t get any control. They don’t get time to pack.

And when one person makes a unilateral decision to disappear, it’s not just the relationship that ends. Everything around it becomes questionable, too. The trust in the shared history, the process of building, repairing, and evolving, begins to erode. We regress. Back into that lonely place with the cold pups and the chaotic mice. Back into the part of us that learned, early, that connection cannot be counted on.

It’s tempting to respond by detaching completely. To believe that no one is reliable. That nothing is truly being built, that it’s all an illusion. That, if everyone is free to vanish, you might as well stop expecting anyone to stay. That’s the narrative we’re taught, especially in Western societies.

That kind of detachment might protect us from pain. But it also flattens the human experience. It teaches us to live half-lives, guarded, self-contained, untouched by the possibility of healing.

I don’t want that. I would rather ache. I would rather cry, plead, and stumble forward. I want to recover and help others recover too. I want to be the kind of person who stays when it matters, who leaves gently. I want this: “We can count on so few people to go that hard way with us.” I want to be those people. I want to be that person.

And because this blog post doesn't have enough quotes already, here’s one more. One of my favorites: Jane Eyre's life has been full of hardship and abandonment. Yet, she heals and falls in love:

“I have for the first time found what I can truly love—I have found you. You are my sympathy—my better self—my good angel. I am bound to you with a strong attachment. I think you good, gifted, lovely: a fervent, a solemn passion is conceived in my heart; it leans to you, draws you to my centre and spring of life, wraps my existence about you—and, kindling in pure, powerful flame, fuses you and me in one.”