DRAFT: Tivoli

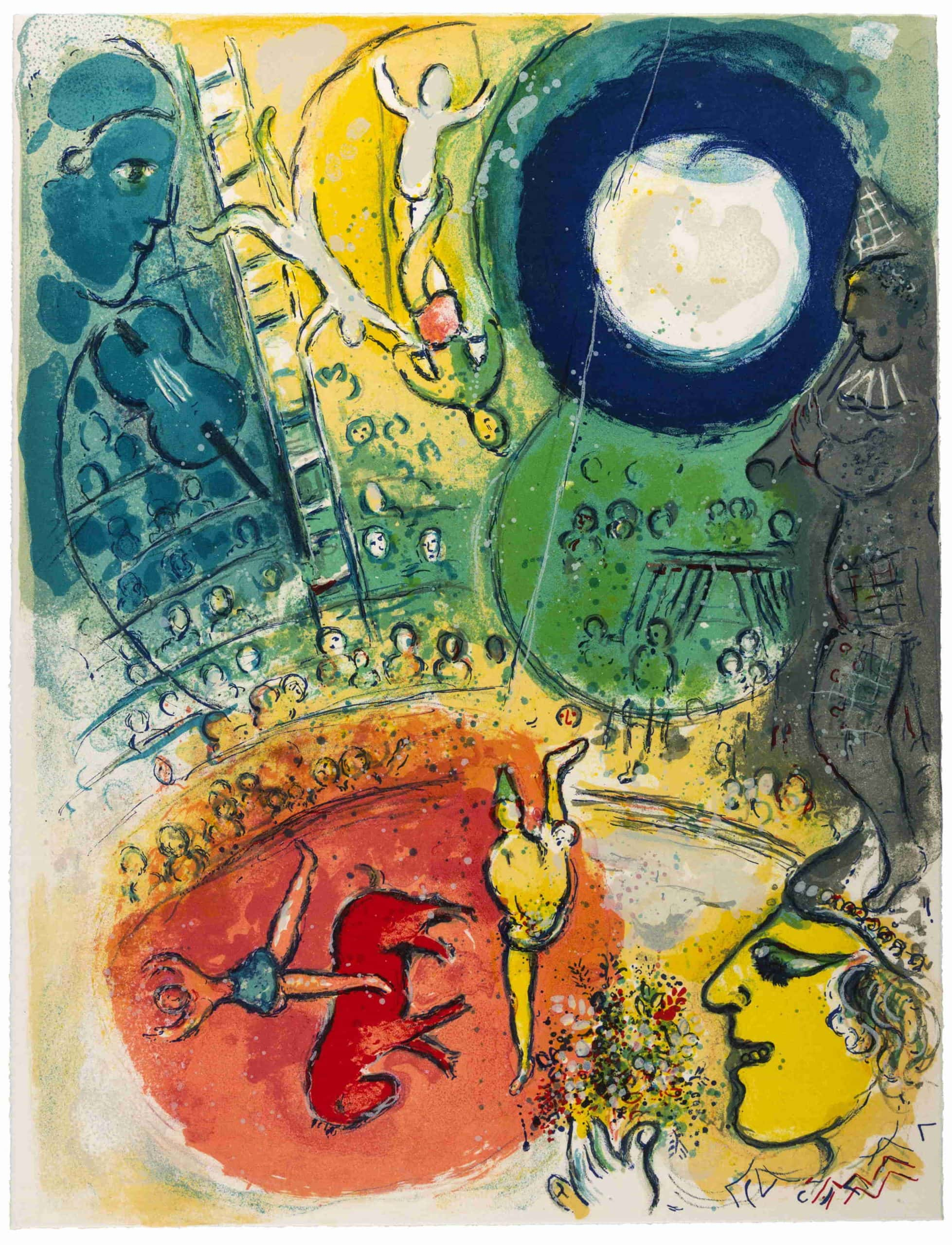

I've always loved amusement parks. To me, (along with the circus) they're pure magic. If I ever get married and, for some reason, decide to have a wedding, it will be at an amusement park.

As a child, I never had the opportunity to experience them. We had only one park in our city, far from where we lived. My mother couldn't drive (women weren't allowed to then), and my father was simply unavailable. So I grew up fantasizing about these magical places.

My first visit came in 2014 or so, on a school trip with my English program. It was a disaster. I didn't understand the amusement park protocols: lines, ride entrances and exits, different passes. Combined with my limited English and being surrounded by 15 other struggling students, the whole experience felt awful. We were adults on a school trip, and I'm sure people thought we were mentally challenged. That day, I decided I'd had enough of constantly having to learn new things: learning to use the subway, learning to order eggs in 10 different ways, and now learning how to have fun????? Fuck that. I declared that I hated amusement parks.

Six years later, I went with my nieces. The experience was completely different. I loved every moment.

The third time was in 2023 with my father, older brother, and youngest sister (which was also such a random combination, given that our family is quite large to end up with this selection). I realized this was my dad's first time at an amusement park, too. Every resentment about my deprived childhood vanished. We spent the entire day, from opening to closing. Four adults riding every attraction together. My siblings hadn't really experienced parks either. That day, I didn't just love amusement parks. I adored them. The whole thing took my breath away.

The fourth time, was earlier this month in Denmark, I finally visited Tivoli. I'd always been fascinated by this amusement park nestled in Copenhagen's city center. It seems like such an indulgent use of tiny city space. Walking through the city, I'd hear laughter and screams of delight. But I'd never entered during my previous three visits. Going alone felt lame.

This time, I had two tickets, one for me and one for a friend who couldn't join my trip. I was sad and disappointed, as I had been looking forward to exploring Tivoli with a friend. I considered selling the tickets, but decided against it at the last minute. If I didn't go, I'd risk developing another negative association with amusement parks. So I went alone, and it was wonderful. I told a friend about that experience and he said: “That trip would’ve made an excellent silent movie. Mona alone in Tivoli is what dreams are made of.” And I agree hehe.

My Tivoli experience inspired this story below. It’s still a rough draft and has been hard to edit. I’m trying to accomplish a lot with this story, but I'm falling short and getting stuck. I promise I'll come back and edit it, and if any of you want to help me, i would 100% welcome that.

The Story

“The little mermaid thought it was a merry journey, but the sailors were of a different opinion.” Hans Christian Andersen

The first thing you should know is that I used to breathe water. Now I breathe air.

The second thing you should know is that in air, gods drown.

It started just like any day, me haggling and trying to sell Tivoli tickets just outside the park. A woman approached with dusty shoes and a pigeon on her shoulder. "Please, I beg you to see my misery," she said, and indeed. I saw her whole life in her eyes: porridge for breakfast, porridge for dinner, a bed shared with four sisters.

She said: "The only thing that happened in my life is monkeys stole me as a baby, the police rescued me quickly, and I was too young to remember the event anyway. This ticket might be the only adventure I'll ever have." This was even more depressing than I expected. I couldn't just give her free tickets (capitalist blood and all), so I gave her a steep discount instead. I sold her both tickets. One for her and one for her pigeon. I watched her go, remembering when I, too, believed one ticket could change everything. Back when I still had a tail and a god.

And now I was ticketless. And very slightly rich.

After I counted my cash and my blessings, I stood just outside Tivoli, relaxed, taking in the atmosphere and people around me. The place was spectacular, but the people were regular. Too regular for a place as spectacular as Tivoli.

After a while, my eyes landed on a man who did not look regular.

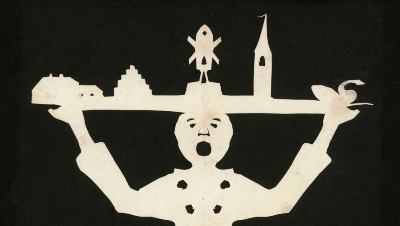

He had a wooden nose. His coat looked like it hadn't been taken off in decades (and honestly, who wears a coat in this weather?). You wouldn't have noticed how strange he was unless you had been watching for too long (which I had).

The crazy old man started coming toward me. He pointed to the crumpled bills in my hand and said, "Well, well, rich young mermaid, would you like to pay me for some entertainment?"

I know I should have walked away. But I'm a tourist. And tourists are the most willingly ripped-off species on the planet. So yes. Of course, I paid him.

I handed over everything. What can I do? My curiosity has always been stronger than my instinct for survival. It's what got me legs in the first place.

Once he took my cash, he reached for my hand. Holding it, we walked into August 15, 1843: Tivoli's very first night.

"First time traveling through time?" the old man asked, not waiting for an answer. "You'll get used to it. Though I suppose mermaids are already accustomed to moving between worlds."

How did he know I was a mermaid? That's when I noticed who he was. Lantern light caught the curve of his nose, the curiosity in his eyes. It was Hans Christian Andersen, there beside me. I was the mermaid, and he'd stepped into his very own fairy tale (though he got the ending wrong).

We joined the masses flowing toward the entrance. People had been waiting in line for hours. The queue bent and coiled around the park like an intestine. Slack in some places, knotted in others.

Everyone looked thrilled and mildly confused. After all, no one in all of human history had seen an amusement park before. There were no amusement park protocols. We were navigating joy without instructions, for the first time.

The crowd was a strange democracy: fishwives beside baronesses, chimney sweeps among parliament members. Some people dripped in gold; others had lice dripping from them. There were unfamiliar animals and people who appeared to have traveled from remote lands.

When the gates opened, we flooded in.

Immediately, humans began inventing practices, traditions, joy, faith, and all. A man started removing his hat and bowing solemnly to every ride he passed. Others copied him.

And one man, on a whim, tossed a coin into the fountain and made a wish. No one had done that before. But others copied him. Somehow, that little guess became a tradition that outlived everyone there and is still in effect today. (Just to keep the historical records straight: that wasn't the first time man had thrown things in water, of course. In my ocean, we found all sorts of things they'd tossed. I just wished they'd thrown coins instead of trash.)

I turned to watch a group of villagers helping a grandma find her teethset. She'd lost them laughing too hard on the trampoline. She was still laughing, gums exposed to the night, while they crawled around looking.

"Look," Hans said, pointing to a crowd around a popcorn machine. "They think it's magic."

And it was. Not the corn exploding into white flowers, but the faces watching, mouths open, eyes wide, discovering that ordinary things can transform. A pickpocket stood among them, so mesmerized he forgot to steal. His empty hands hung at his sides like broken wings.

The innocence hurt to watch. It was like seeing myself that first day with legs, believing walking would be just like swimming through air.

Hans led me up a path that spiraled inward and upward. The laughter below grew distant. Half the visitors had stopped at the entrance attractions, content with simple wonders. But some of us needed more. Popcorn popping wasn't jaw-dropping anymore; we couldn't laugh at the farting concert that delighted the farmers.

"The entrance attractions are charming, but crude. Child's play, really," Hans said. This new area was different. Actions weren't spontaneous and first-order anymore. They were intellectual, calculated, not just reflexive.

Here, the artistry was so masterful it became paralyzing. A woman stood frozen between two pathways, unable to choose. Both routes were so perfectly designed, so exquisitely promising, that the decision became impossible. Moss had begun growing on her shoes. Her children waited beside her, noticeably taller than when she'd first stopped, their faces aging; they learned that some choices take lifetimes.

Near a pavilion displaying intricate mechanical puzzles, I spotted a man in fine clothes hunched over what looked like a cube covered in colored squares. His fingers moved frantically, twisting sections, trying to align the colors.

Hans said, "This bald gentleman is in the captive balloon business. It's taken him halfway around the world with excellent profits. Not bad for a shepherd from the Arabian Peninsula." He looked so absorbed and, completely oblivious to his growing audience.

A velvet stage caught my eye. A woman pressed a red button and the room exploded—applause, gasps, a standing ovation. She'd done nothing, but for thirty seconds she was everything. When the noise faded, she pressed again. And again. I watched until her fingers started to bleed.

"It's fucking bloody, let's keep going," Hans said and walked fast. Before following him, I took one quick look back, the woman with moss on her shoes still hadn't chosen a path. Quite sad.

We continued walking. The third area smelled different. It wasn’t not caramelized apples anymore, but metal shavings and ink, sawdust and sweat. That intoxicating smell of human creation was everywhere, sharp as brine.

The sounds had changed, too. No longer laughter or the silence of mental absorption, but the steady hammering, grinding, precise instruments at work.

"Below, people experience wonder," Hans said. "Here, they build it."

A woman with ink-stained fingers was sketching mechanical drawings for what would become the carousel. She'd calculated the precise speed for exhilaration without nausea, the exact height for horses that would make children feel magnificent without terrifying them. Her papers were covered in equations—joy reduced to mathematics, wonder to engineering.

Nearby, a team of engineers solved the problem of artificial lightning for a storm-simulation ride. They'd harnessed actual electrical forces, tamed them, made them perform on schedule eight times per day. Thunder on demand. Lightning that struck precisely where intended, when intended, for exactly the duration that maximized thrill.

I found myself mesmerized by their devotion. I could see it in their faces—the addictive thrill of forcing the impossible to behave.

I was lost in this thought when a massive sound shook the air. What was that? I looked around. The workers paused for a moment, then most returned to their hammering and sketching. The cost of looking away was probably too high.

Hans touched my elbow. "Shall we?"

We climbed toward the sound. As we walked, I noticed we weren't alone. The toothless grandmother from the entrance was climbing too, no longer laughing, but still toothless. Behind her, the woman from the velvet stage, her bleeding fingers wrapped in stained cloth. A handful of others, but not many.

What an odd group we made chasing this scary sound. Not the brave ones or the wise ones. We were simply the restless ones. The ones who had to touch the stove to truly believe in heat. Who asked "and then?" until there were no more answers. Who needed to follow that sound higher, we just couldn't let any mystery stay mysterious. And yes, sometimes those people are toothless grandmas.

We reached the source of the sound. A clearing at the summit. And there came a wave of men. Over 180 of them, a swath of frightening, evil-looking, good-for-nothing, possibly threatening characters. They had been hired that morning from the city's mental asylum. They wore overalls and reeked of antiseptic, sleep and yesterday's despair. They pushed an eight-wheeled flatbed that groaned under impossible weight.

The crowd wondered what they might find once the package was unwrapped. Surely something whose very size promised it could not disappoint.

When the tarp slipped, the crowd saw its tongue first, flat and massive. It fell like a tree. Then one eye clouded like old milk. It took fifteen minutes to unveil it entirely, the men working in eerie synchronization. When they finished, they stepped back and announced together in monotone: "The evening's main attraction."

It was a whale. Dead. Massive.

"Oh my god," I whispered. No. Literally, my god. That whale is my god. This is what I worshipped as a mermaid in the ocean's depths.

My knees forgot how to hold me. I sank to the gravel, my human legs folding wrong, nothing like the graceful curl of a tail.

A child poked his blowhole with a stick. The hole made a wet, deflating sound.

"Stop," I whispered, but no one heard.

A merchant had already set up a booth: "Genuine Whale Oil! Direct from the Sacred Beast!"

I pressed my palm against the whale’s side. I waited for something: a shudder of recognition, a cry for help, even a curse for my betrayal. Nothing. Just meat under my hand. A bloated colossus, hauled through gravel, mud, music, and mortal eyes. Drowned god, dragged whale. My deity, their spectacle.

The world hadn't killed my god. I had. By choosing to see beyond the borders of my small underwater realm, by getting so dazzled by the details of human wonder. I had witnessed science and art and technology, and marveled at the complexity of their world. All of it is happening right here, in this single night, in this single park.

In my ocean, questions floated up like bubbles until they hit the surface and burst. Every curiosity had a boundary: the water's edge, where blue ended and air began.

But humans? They swam in our ocean, visited our whale. Then they climbed out, scaled their mountains, and looked up at skies that went on forever. Unlike us, their questions didn't hit ceilings. Their questions rose into infinite space, multiplying like stars. And with just ten fingers, soft, absurd little sausages of flesh, they pointed at that endless dark and counted galaxies. A billion stars. A trillion. Numbers so large my underwater mind couldn't hold them.

If humans could invent meaning this easily, this beautifully, this completely, then God, it turned out, wasn't needed anymore.

I wanted to weep for him. Instead, I found myself wondering how they had transported something so massive, admiring the engineering required to drag a god from the depths to the surface.

Even my grief had become sophisticated and curious.